PART 2: Language in ‘Crisis’

An advocate’s reflections on campaigning within a child-rights framework

Lilly Carson has been interning with the Global Campaign to End Child Detention since September 2017. She manages the Campaign’s social media accounts and assists with campaigning. Lilly is from Melbourne, Australia, and has a Masters of International Relations from the University of Melbourne. One day Lilly hopes to work in a role supporting the development and implementation of policies that uphold the human rights of all migrants and internally displaced people.

Migration is nothing new, and yet suddenly it’s all over our news.

Whether fleeing war, persecution or economic deprivation, people will continue to cross borders in search of a better a life. The problem with this moment in history is that society perceives migrants and refugees as burdens in the first place. The latest ‘crisis’ framework only cements this point of view.

When the term ‘migrant crisis’ rose to prominence in the middle of 2015, I was in Berlin completing an internship in government. I was tasked with reporting on this so-called ‘crisis’ and analysing how the public and political spheres were reacting to it.

Each day I would sift through news stories, in which people fleeing war were described as ‘swarms’ and ‘floods’. Reactionary headlines were paired with images depicting people on the move as an invading mass.

People were divided. On one side, there were heartwarming stories of locals greeting refugees with open arms and cheers at train stations. On the other, there were hateful stories of arson attacks on refugee homes.

I have no doubt that these words – crisis, swarm, flood, invasion – contributed to feelings of fear, panic and xenophobia. To this day, the mainstream media continues to frame the narrative of human mobility in terms of security, nationalism and scarcity. This has the effect of limiting compassion towards refugees and migrants because we don’t perceive them as individuals.

Source: ‘Framing Equality Toolkit’, ILGA Europe and Public Interest Research Centre.

In the final week of my internship, I met a little girl at a refugee home on the outskirts of western Berlin. She had only been in the country several months but her German was almost fluent. She giggled at my funny accent and shyly told me she loved going to school.

I was able to connect with this girl because we had a conversation about normal, relatable things. But most of our audience will never have that opportunity. This is why we need to pay close attention to how we frame the act of migration in our external communications.

We don’t use the phrase ‘migrant crisis’ because it avoids placing blame on the actions, or lack of action, on the part of national governments.

This should be remembered as a time when wealthy nations failed to collectively uphold their responsibility to respect international law and provide protection to people in need. This is not a migrant crisis, but a crisis of migration policy.

We’re talking about women, men and children, who all have rights, so don’t make them the problem. The language of the Campaign must avoid suggesting that migrants and refugees are to blame for attempting to access rights that they shouldn’t need to fight for. That’s exactly why they are called fundamental human rights. They should be a baseline for all.

Two of the Campaign’s communications aims are to build a movement around ending child detention and to urge governments to create child-friendly alternatives to immigration detention. If society thinks of child migrants and refugees as a ‘crisis’ and a ‘burden’, then our audience is going to be less likely to relate to their humanity and to understand what their needs are. When people are described as masses, we are less likely to be compassionate.

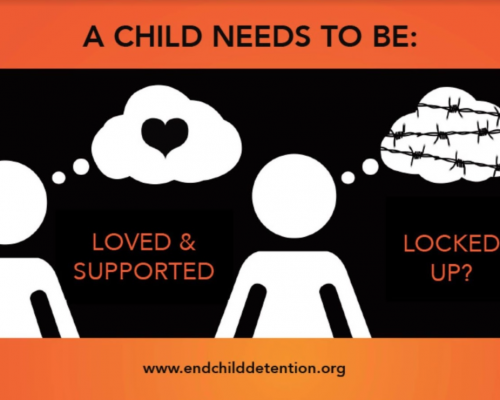

Most people react to issues relating to migration in an emotional way. Sure, we could overwhelm our audience with facts and figures that show that wealthy nations have the capacity to deal with large numbers of asylum seekers, refugees and migrants. But people are more likely to change their minds if we use language that provokes positive emotions (e.g. ‘children deserve to be loved and cared for in the community’), as opposed to negative ones (e.g. ‘child refugee crisis is putting a strain on local resources.’). Positive frames evoke hope and human connection, while negative frames inflame a sense of urgency, panic and isolation.

Of course, negative frames can be useful because they easily grab people’s attention. But ‘negative emotions also hinder the memory of the audience: people will remember fewer facts from a message’. When used effectively, the right language can persuade people (and hence, governments) to shift their perceptions about children and migration. And isn’t this exactly what our campaign is seeking to achieve?

In part 3 of this blog series, I discuss why it’s about time that we say goodbye to child detention as a last resort.

Further reading:

- Framing Equality Toolkit via Public Interest Research Centre

- Five point guide for migration reporting via Ethical Journalism Network

- Words Matter via Picum

- Words that Work via the ASRC

- It’s Time to Stop Compartmentalizing Refugees and Migrants via Refugees Deeply

- People Can’t Flood, Flow or Stream: Diverting Dominant Media Discourses on Migration via Border Criminologies

- Words Make A Difference via The Global Campaign to End Immigration Detention of Children

- Children’s Rights: Guide for NGOs via Child Rights International Network

- How to Talk Persuasively about Child Rights via UNICEF Australia