Central American Children Seeking Refuge

Translated from original post in Spanish written by guest blogger Natalia del Cid

Living in Central America is a daily struggle. Actually, ‘living’ isn’t the right word. It’s really more like ‘surviving’ if we’re talking about children who are faced with extreme poverty, making them vulnerable and increasing their likelihood of migrating. Living alongside multiple homicides isn’t pleasant. You know, more than that, it’s knowing that the next crime committed could affect you, your family, your neighborhood.

The gangs in Central America are criminal groups (also deemed ‘terrorists‘ by the El Salvador Supreme Court in August 2015) that make their living by extortion and drug dealing. These groups originated in Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles, California in the 80’s, and later many of their leaders were deported back to Central America in the 90’s, where they returned to poverty, unemployment and social exclusion.

Living in Central America is a daily struggle. Actually, ‘living’ isn’t the right word. It’s really more like ‘surviving’…

Neither the Central American governments or society understood these young people who had been deported, and their reaction to them was violent. The gangs became stronger in marginalized, poor neighborhoods, breeding grounds that had been abandoned by the State. Now, decades later, these gangs grow even stronger, as they force young people who struggle with poverty and often come from broken homes to join. Now they don’t just make their living by extortion and drug dealing, but also by terrorizing public schools, forcing other children to commit crimes, and making even teachers fear for their lives. In Central America, these gangs are know as ‘maras.’

Every night there are many Central American children who sleep in their bed for the last time. They know that the next day they’ll begin a long journey, sometimes accompanied by friends or family, but often alone — without anyone. They flee. They escape the daily violence that continues to worsen. They don’t want to be the next child to be forced to join the maras. They don’t want to be the maras‘ girlfriends. They don’t want to end up in jail or in the cemetery.

These children’s biggest fear is staying in Central America.

Source: Blog MidiaeProfecia

Central American refugee children’s biggest nightmare isn’t the journey. It isn’t Mexico either. These children’s biggest fear is staying in Central America: that stretch of land so violent that it sends away thousands of its residents, each year. It’s a flow that grows and intensifies with the violence. It’s a route for survival that people have been taking for decades: migration. Central American children flee for their lives because they know that they are in danger if they stay at home. Some are witnesses of crimes; others don’t want to join criminal groups. Others simply miss their parents.

Their families, with much sacrifice, save what little of their earnings they can working undocumented in the United States in order to provide for their children in Central America — to help them survive the insurmountable poverty — to maintain family ties — so that their own children don’t forget them as parents, as providers. But the children don’t forget. They simply want to hug their parents again.

How is it possible to deprive Central American children of their freedom when they’ve committed no crime?

What will happen to these children when they leave Central America? Will they be given protection and refuge in other countries? How can we help them reach their parents? How can we help them survive the violence in Central America? Why are Central American children detained in the United States and Mexico? How is it possible to deprive Central American children of their freedom when they’ve committed no crime? Isn’t it more costly to detain Central American children than to give them protection and refuge? What type of society locks up children who are fleeing from violence?

Photo by: Ivan Castaneira (Twitter: @i_chido)

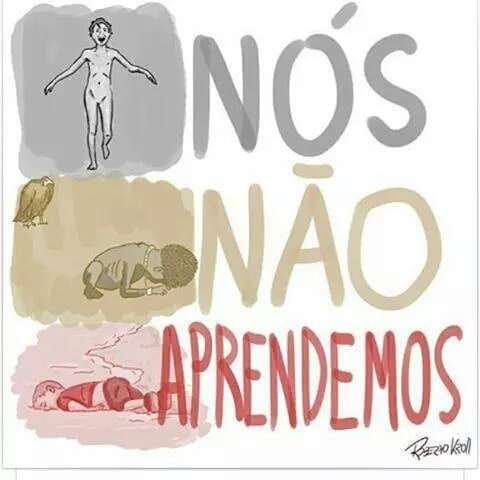

This summer, an 11-year-old Salvadoran child died while trying to cross the desert between Mexico and the United States. This wasn’t purely a natural death. There are many deeper causes, ranging from the violence that forced him to flee from his home, neighborhood and country, to his family’s poverty, to the persecution he suffered in Mexico as a migrant, and the desperation felt by his parents that led them to send their son fleeing for his life through a desert. If we don’t want to find more child cadavers in the desert of our indifference, the correct thing to do is to stop detaining them, stop chasing them, stop sending them back to dangerous situations. The correct thing to do is to open our homes to them.

NATALIA DEL CID is a Salvadoran researcher and advocate for Central American migrants in Mexico. She is co-editor of the website Migration Systems and associate researcher for the Central American Institute of Social and Development Studies (INCEDES). She has also participated in the Caravans of Central American Mothers in Search of their Migrant Children who have Disappeared in Mexico. You can follow Natalia’s work on Twitter at: @delcidnatalia